Ecological Underpinnings of Wealth

Question: What’s the best way to improve the economy of a developing country?

Answer: Provide better healthcare to its citizens and conserve its biodiversity

Better healthcare?!? If you’ve been listening to the conversations from the left and right in the U.S. Capitol, you might well wonder whether better access to healthcare destroys economies, rather than helping them. And how can biodiversity conservation help? You don’t see gorillas working on the line at the auto plant or anyone betting on polar bear futures at the IntercontinentalExchange (ICE).

You’ve never read about it in any economics textbook, nor will you likely read about it in any finance periodical, but in fact, this is the essence of the message of an article in PLOS Biology published last year by Matthew Bonds and colleagues entitled “Disease ecology, Biodiversity, and the Latitudinal Gradient in Income”.

Some of the worst human maladies are caused by parasites and pathogens that interact with animal vectors (e.g., ticks and mosquitoes) and/or alternative hosts (e.g., birds that harbor H5N1 influenza). Contrary to popular belief, we humans don’t sit at the top of the food chain but instead are fed upon by numerous species that are themselves embedded within a complex ecological web.

We usually think that more prosperous countries can afford to keep these parasites at bay via better nutrition, healthcare and mitigation. However, the analyses by Bonds and colleagues flip this on its head to show that it’s healthier people who are able to make their countries more prosperous.

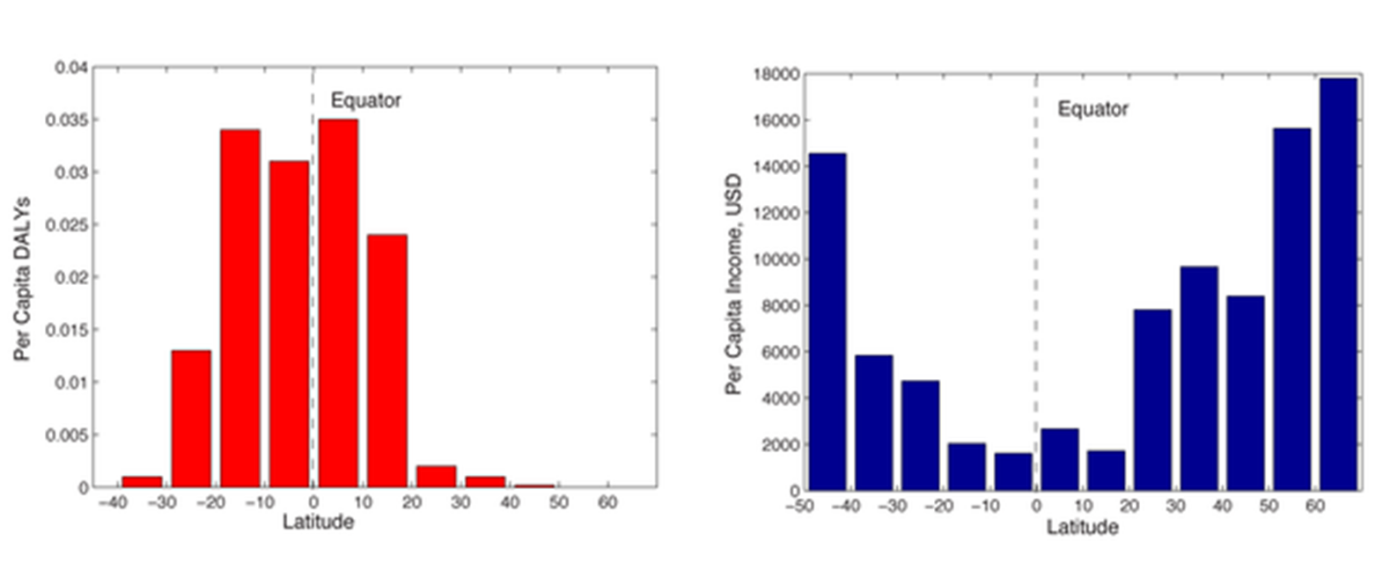

Just how were the authors able to disentangle these interconnected factors? They examined the well-known increase in the burden of vector-borne and parasitic diseases (VBPDs), an increase that occurs as you move towards the equator and that is mirrored by a decrease in per capita income (see below).

Although these correlations between health, wealth and latitude were well-known, it wasn’t clear which was the cause and which were the effects. In fact, a prominent hypothesis among economists (at least Western ones) is that these relationships had more to do with the timing of the history of colonization and the distance from Europe than anything else.

To tease apart the cause/effect relationships between wealth and infectious disease, Bonds and colleagues used a form of statistical analysis (called structural equation modelling) to evaluate data from 139 countries across the globe, including socio-economic data provided by the World Bank and data on the burdens of VBPDs from the World Health Organization. By comparing a series of potential causal relationships from the data that included a lot of variability between countries, even at the same latitude (see map below), they were able to conclude that disease burden appeared to be a primary causal factor for why more equatorial countries have lower per capita income.

![Global map showing the distribution of disability adjusted life years lost to parasitic and infectious diseases from 2002. Data compiled by the World Health Organization. Source: Lokal_Profil [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://biologue.staging.plos.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/05/Global-DALY-2002-300x132.png)

A second focus of this paper addressed the role of biodiversity in influencing the burden of infectious disease. An increasing number of scientists and conservationists have come to believe from recent evidence that biodiversity might actually decrease your chances of falling sick from VBPDs. Recently, however, some disease ecologists have argued against this idea since biodiversity can increase risk, and the diversity and abundance of parasites and pathogens increase as one goes towards the tropics.

At the cusp of this controversy, Bonds and colleagues knew they had the appropriate large-scale data and analytical tools to address this issue. They found that VBPD burden and biodiversity were indeed positively correlated globally, because both correlated with decreasing latitude. When they corrected for latitude, however, they found the opposite relationship; countries at similar latitudes had an inverse relationship between biodiversity and VBPD burden, so as diversity goes up, disease goes down. Though speculative, this suggests that biodiversity conservation might have a direct positive impact on a country’s economy by increasing the health of its workforce.

Unlike some of the other studies highlighted in the 10th Anniversary Collection, this study was published too recently to know what eventual impact it will have on its field, and whether it might even instigate the revisiting of international policies. What is clear, however, is that much as we might like to think that our species is no longer controlled by fundamental ecological principles, their influence is pervasive. Much of economic theory is still based on Adam Smith’s perspective on the “Wealth of Nations”, which emphasized that self-interest could benefit the entire group via the “invisible hand” of market forces. The analyses of Bonds and colleagues’ suggests that the invisible hand of pathogens and parasites might have just as pervasive an influence on the global economy.

See the Tenth Anniversary PLOS Biology Collection or read the Biologue blog posts highlighting the rest of our selected articles.

See the Tenth Anniversary PLOS Biology Collection or read the Biologue blog posts highlighting the rest of our selected articles.

Bonds MH, Dobson AP, & Keenan DC (2012). Disease ecology, biodiversity, and the latitudinal gradient in income. PLoS biology, 10 (12) PMID: 23300379

Jon Chase is an ecologist interested in patterns of biodiversity and its underlying processes. After more than a decade in academia, his current hiatus is filled with independent research, freelance writing and editing, and spending lots of time with his two young children.