Chromosome Biology: You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby

It might be hard to believe, but 2015 marks ten years of PLOS Genetics! To celebrate ten years of hard work, research, and immense dedication from our Editorial Board, we are featuring posts from ten of our editors about the discoveries that they have found exciting and paradigm-shifting in the last ten years. First up is Beth Sullivan, PLOS Genetics Associate Editor, on the last ten years of chromosome biology.

I saw my first mammalian chromosomes under the light microscope when I was a high school student during the 1980s. The 46 X-like bodies stained with Giemsa dye were evenly distributed in the microscope’s field of view. They were beautiful and I was enchanted. As I inspected them more closely, I wondered why the chromosomes were different sizes. Why did they have different patterns of light and dark bands? Why were they pinched in the middle? Then and there, I vowed to understand these questions, and pledged to study chromosomes for the rest of my life. (Teenagers can be so dramatic.)

Within ten years, I was immersed in the field of chromosome biology. I went to graduate school, where I ultimately worked with a leading cytogenetics researcher. Under his mentorship, I studied the formation and behavior of a common human chromosomal abnormality known as Robertsonian translocation.

In the 1990s, chromosome biology was mainly defined by cytogenetics – karyotyping by G- and R- banding. In 1991, FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) was developed. With the help of molecular cloning and PCR, FISH provided a way to fluorescently visualize chromosomes or specific parts of chromosomes, as well as identify abnormalities.

At the same time, other methods to study chromosomes were being used elsewhere, particularly by Ulrich Laemmli and his protégé William Earnshaw who leveraged biochemical and high-resolution microscopic approaches to study the chromatin basis of mitotic chromosomes.

By the time I started my postdoc with Gary Karpen at the Salk Institute in the early 21st century, it was possible to look at chromosomes in three dimensions or as stretched DNA or chromatin fibers, and it was even possible to build chromosomes from scratch. Today, genome editing technologies like CRISPR and TALENs are making it feasible to quickly create and visualize almost any type of genome rearrangement.

When I was asked to write about one discovery that I considered the most exciting in chromosome biology within the last decade, I quickly realized it would be difficult to choose just one study. Although I was tempted to select one of the many advances from my field of centromere biology*, I instead selected a study that continues to excite me every time I re-read the manuscript. It’s the one that causes students to say “wow!” whenever I teach it in my human genetics or medical genetics classes.

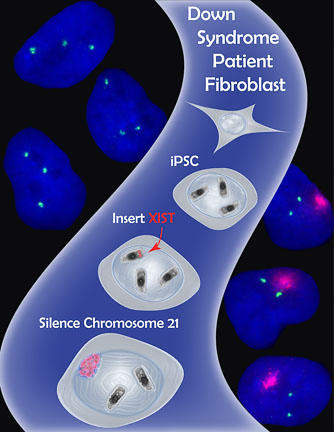

- The Lawrence Lab’s strategy to apply X chromosome dosage compensation to Trisomy 21. Using genome engineering (Zinc Finger Nucleases), the lab inserted the XIST gene into the extra chromosome 21 in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a Down Syndrome patient. Excitingly, the XIST gene was transcribed and the long non-coding XIST RNA coated the extra chromosome 21, shutting off gene expression and shifting chromosome 21 gene dosage toward a normal diploid state. (Figure used with kind permission of Jeanne B Lawrence)

This pioneering work came from Jeanne Lawrence’s group and was published in the journal Nature in 2013 (Jiang J et al. Translating dosage compensation to trisomy 21. Nature 500:296-300; freely available through PMC).

The premise of the study was to explore “chromosome therapy” as a strategy to correct genetic imbalance created by trisomy (a state in humans in which there are 47 chromosomes instead of the normal 46 in each cell). The researchers focused on Trisomy 21, or Down Syndrome, the most common trisomy in humans (1:300 live births).

Down Syndrome is defined by the presence of an entire or partial copy of an extra chromosome 21 (HSA21). Patients have intellectual and cognitive disabilities, as well as heart defects, motor impairments, blood disorders, and increased risk of early Alzheimer disease. The syndrome exhibits vast phenotype (symptomatic) variability that remains unexplained. This is partly because of incomplete knowledge of Down Syndrome critical genes and the cell and developmental processes affected by increased HSA21 dosage.

The Lawrence lab is probably best known for studies of X chromosome inactivation (XCI), the process by which one of the X chromosomes in mammalian females is functionally silenced. This event equalizes gene dosage between females (XX) and males (XY). XCI largely depends on the expression and spreading of a large non-coding RNA called XIST exclusively from the inactive X. XIST RNA moves from the site where it is produced and spreads along the length of the X. Its appearance and distribution on the inactive X is accompanied by a series of epigenetic (sequence-independent) protein and DNA changes that essentially turn off ~700 genes on the chromosome.

In the 1990s, cytogenetic studies of translocations between HSAX and autosomes (non-sex chromosomes, i.e. X or Y) had shown that XIST could spread, at least partially, into autosomal material and silence genes. The Lawrence group speculated that insertion of XIST onto one of the extra HSA21s in cells from a Down Syndrome patient might shut down the chromosome. This would result in a cell that contained only two functional HSA21s.

The group introduced nearly the entire XIST cDNA (21kb) into cultured induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a male Down Syndrome patient. To ensure precise insertion of XIST into HSA21 only, they used genome-editing tools called Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs). These modified proteins were engineered to recognize a specific DNA sequence on HSA21. They would create a break at this sequence that was then repaired by inserting the cassette containing the XIST gene.

Amazingly, the genome editing strategy was successful! XIST RNA was produced on the targeted HSA21 and it visibly spread over the entire HSA21, recapitulating many of the epigenetic features normally associated with an inactive X. Even more exciting, the authors showed that HSA21 genes, including APP, a gene linked to Alzheimer’s disease, were silenced on the XIST-targeted HSA21.

The chromosome silencing strategy in iPSCs also revealed new information about how the extra HSA21 affects brain development. Corrected neural progenitor cells showed higher levels of neural progenitor cell growth and proper rosette formation compared with uncorrected cells that took much longer to grow to the same cell number and to form rosettes. Because neurogenesis follows a prescribed temporal path, these findings imply that some of the irregularities in Down Syndrome brains may be due to delayed developmental timing of neurogenesis.

A seminal study of this type naturally leaves many unanswered questions – Are other features of Down Syndrome corrected? Is gene silencing on the HSA21 consistent across the entire chromosome? Despite these unanswered questions, what made this a fascinating and notable piece of work to me was the way in which it elegantly united three distinct biological processes – X inactivation, gene silencing, and consequences of chromosome abnormalities – into a beautiful story that is grounded in basic research, but cues up the translational option of a unique type of gene therapy.

From this clever line of experimentation, we now know that a silencing mechanism specific to the X chromosome can be co-opted to silence genes on an unrelated chromosome. Could this occur on other chromosomes? Could one partially silence a chromosome or a subset of genes on a portion of a chromosome? How viable will this therapy be in a whole organism?

I expect to read more from this group and others as they extend and improve the technology. And if nothing else, I look forward to more inspiring and groundbreaking studies like this one in the next ten years of chromosome biology!

——————————————-

*If you have the time, check out these studies that rocked the chromosome biology world in the last decade and made my short list for this post:

1. Controllable Human Artificial Chromosomes (2008)

2. Creation of Neocentromeres/De Novo Centromeres at Unique Locations (2009, 2013)

3. The Three-Dimensional Genome (3C, 4C, 5C, HiC)

[…] https://blogs.staging.plos.org/biologue/2015/02/24/chromosome-biology-youve-come-a-long-way-baby/ […]

[…] what their hopes are for future research. The first post in this series is from Beth Sullivan on the last ten years of chromosome biology, which provides an exciting insight into the challenges and achievements this field has seen over […]