Conservation Research: Aiming at the Wrong Target?

Six years ago, the Convention on Biological Diversity adopted a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity, which included 20 specific goals, known as the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. In a recent PLOS Biology Perspective, Kerrie Wilson and colleagues seem to throw a bucket of cold water in the faces of those feeling optimistic about attaining one goal in particular – Target 19.

This Target – which states, “By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied”– is not really about biodiversity or conservation outcomes, but about accessing, sharing, and communicating biodiversity knowledge.

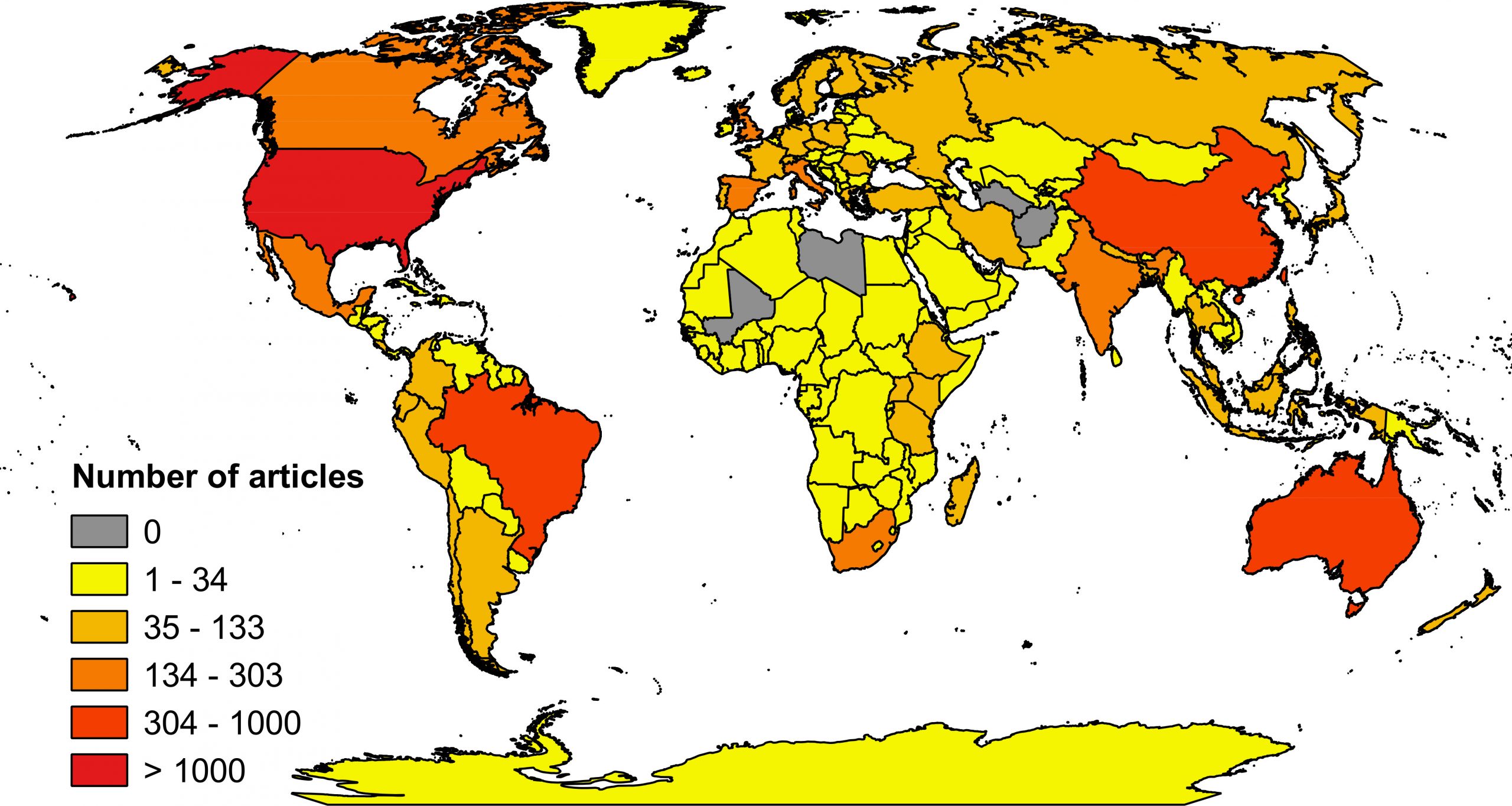

What then is the state of research and scholarship in conservation science with regard to knowledge sharing, transfer, and application? Wilson and her co-authors conducted a survey of over 10,000 scientific papers on conservation published during 2014, comparing the topic countries of these papers with lists of countries that have high biodiversity and importance for conservation. They found that, with just a few years left to go, there are three key areas inhibiting progress toward Target 19 by 2020:

1. Biodiversity research isn’t happening in the highest priority areas for conservation

The knowledge that matters most to conservation science continues to elude the scientific literature. A disproportionate amount of biodiversity research takes place in funding-rich, but less biodiverse, places such as the United States and United Kingdom. Meanwhile, in areas of critical importance to biodiversity conservation, such as Indonesia and Madagascar, a dearth of published research has slowed the flow of knowledge on biodiversity in these areas to a trickle. The places most important for biodiversity conservation make up a relatively small percentage of published conservation literature compared to less biodiverse countries, such as the USA and the UK.

2. Most published conservation studies aren’t widely accessible

Researchers from not-so-rich-institutions (often in areas important for conservation) suffer under the hegemony of the publishing industry. 88% of research based in countries of high biodiversity importance are not open access, making the sharing and application of knowledge out-of-reach to many, including the public and researchers working in underfunded institutions. The open access model may offer a solution on the supply side; however, open access publication fees may be out of reach to some researchers working in key conservation areas. Connecting the public to research findings is vital for meaningful, on-the-ground change, but these findings are less frequently communicated across social media and other publicly accessible channels of information.

3. Exclusive practices across conservation fora have stymied knowledge exchange

Research conducted in biologically diverse countries is rarely led by in-country nationals. Conducting fieldwork outside one’s native land can be politically, socially, and logistically fraught, so why aren’t we seeing more partnerships between US and UK researchers and institutions in biodiverse countries? Target 19 strives for the application of new knowledge, but conservation communities have been slow to engage experts from outside the centers of major funding via working groups, conferences, symposia, etc. The exclusion of researchers hailing from conservation-important areas from research collaborations and leadership in international fora points to an apparent cultural clumsiness on the part of the scientific community, as well as the need to adopt practices that better facilitate the exchange knowledge and engage the particular expertises of conservation scientists living in some of the world’s most diverse places.

The authors conclude that these three sources of bias in conservation science have the potential to significantly inhibit progress toward meeting Target 19 and require an intentional and diverse set of reforms. Some of these solutions include increasing support for – and investment in – open access publishing, conscious and proactive inclusion of stakeholders from key biodiversity areas in conservation research and international networks, as well as refocusing our attention and resources toward areas of great biological diversity and great knowledge gaps. Taking some mindful steps toward making knowledge production more broadly accessible and inclusive are major imperatives for improving conservation outcomes via Target 19 of the Convention on Biological Diversity.