How do you like your fish? Phylogenised!

The bony fishes are one of the success stories of life on planet earth, diverse in shape and habit, and thriving in almost every body of water on the globe. Estimates of the number of distinct species tend to be around the 30,000 mark, but the real number is likely to be much higher. We eat them, admire them in aquaria and on David Attenborough films, and threaten their existence with our way of life. But how did this flowering of supremely adapted aquatic and marine animals come about? Two papers just published in PLOS Currents Tree of Life give us the most comprehensive fish family tree yet.

Taxonomy, or the hierarchical categorisation of species according to their perceived similarity, has been with us for centuries, sometimes pursued by the gentle clergyman trying to document God’s creation. Taxonomy’s hard-nosed descendent, phylogenetics, aims to re-jig this endeavour in the light of the recognition that these hierarchical similarities didn’t arise by chance, but instead reflect the real underlying hierarchical divergence of things that are related, by descent, via common ancestors. Dogs look more like cats than either looks like a frog – not because an omnipotent being liked to make his creations in boxed sets, but because the dog ancestor split from the cat ancestor after the dog/cat ancestor split from the frog ancestor.

Since that recognition, phylogenetics has revisited the question of establishing the true “Tree of Life” – a pattern of relatedness that reflects the actual order of divergence of ancestors from each other, giving rise to the richness of extant species that we see around us today and those extinct ones whose traces we find in the rocks below our feet. While you can use data about almost any aspect of an organism to make a phylogenetic tree, most studies tend to use genetic sequence data because of its sheer abundance, relative objectivity and statistical tractability.

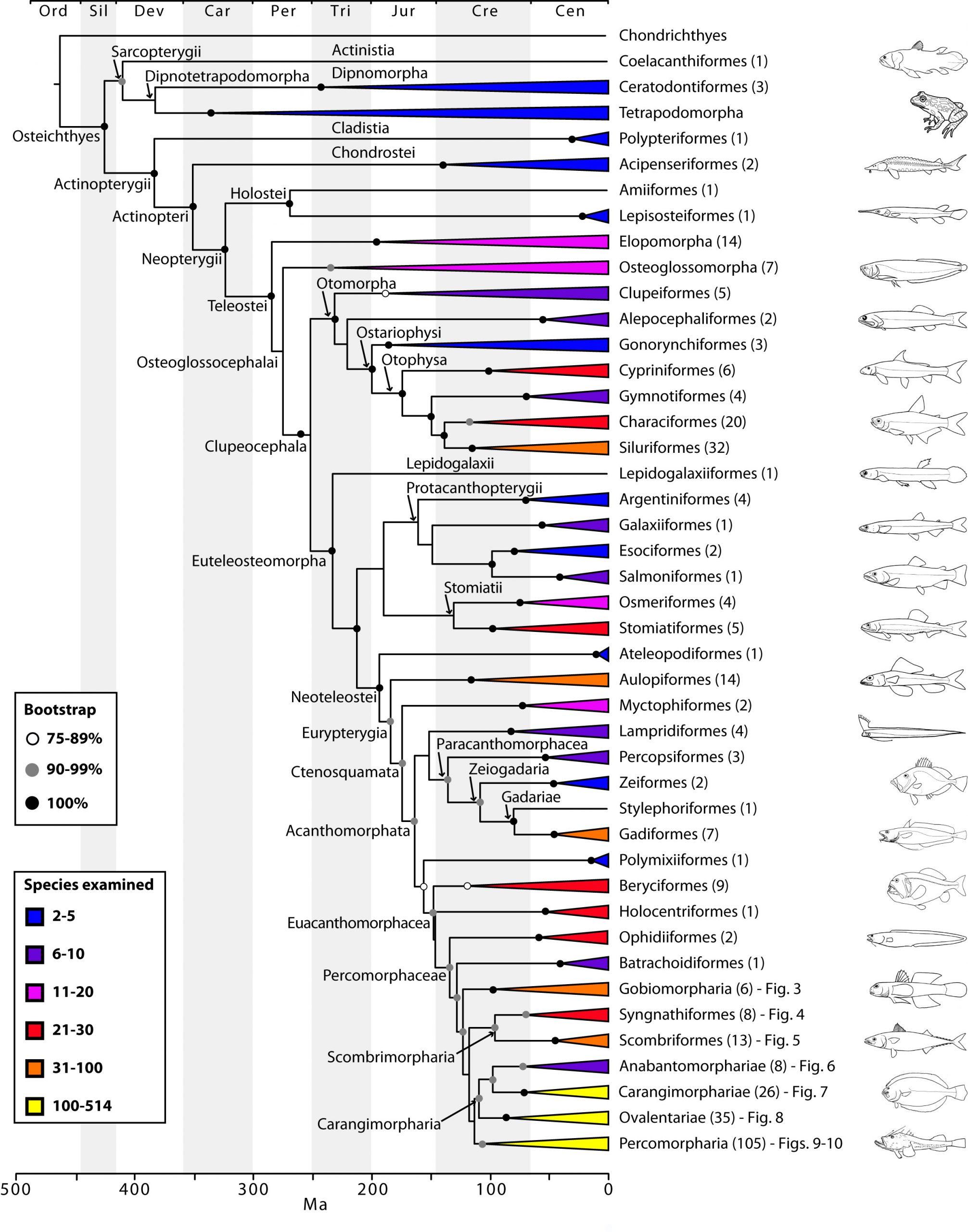

Two papers from Ricardo Betancur-R., Richard Broughton, Guillermo Orti and colleagues, published last month in PLOS Currents Tree of Life (Betancur-R et al., Broughton et al.), aim to provide a definitive answer. This massively comprehensive survey takes in 1410 separate species of bony fish, adding in four tetrapods (human, mouse, opossum, frog) and two non-bony cartilaginous fish (shark, ray) for good measure. They use sequences from twenty-one different genes to give a high-resolution and strongly supported family tree of the extant bony fishes that live on our planet. They also use data from the fossil record to pin down the likely timescale of key divergence events in the tree.

The papers contain a vast amount of information, and the sheer scale and resolution of the study means that the tree has to be broken down into many sub-trees to be presented on paper – a clear case for the infinitely zoomable tree viewer, OneZoom. The one aspect that I’d like to pick out for this blog post is the deepest split in the bony fish family tree – the one that gives rise to Actinopteryigians and Sarcopterygians. The Actinopterygians are the things that you see in the fishmongers – fish with a capital “F” – ray-finned fish. The Sarcopterygians, however, are a really interesting bunch. They comprise coelacanths, lungfishes and tetrapods like you and me. Fish that have gone places.

The papers show conclusively that the Actinopteryigians and Sarcopterygians are indeed distinct groups (“mutually monophyletic”), that lungfishes, rather than coelacanths, are our closest cousins, and that the split between these major groups can be dated to 427 million years ago in the Middle Silurian. We left the coelacanths behind 18 million years later in the Early Devonian. Meanwhile, our more distant ray-finned cousins, the Actinopterygians, started to break out into their oldest extant groups, with birchirs and reedfish peeling off in the Late Devonian, sturgeons and paddlefish in the Early Carboniferous and gars and bowfin in the Middle Carboniferous.

There have been many phylogenies of fish to date, and there are sure to be many more in the future (the addition of more species and the use of more genes per species would trump these studies). However, with 1093 genera from 369 families, representing all known orders, the PLOS Currents papers are close to providing a definitive picture, and have the potential to provide a solid platform for future comparative studies of these amazing animals.

The other thing perhaps worth mentioning is the way in which these papers were published – PLOS Currents is a strand of PLOS that shares some attributes with conventional publishing – it’s fully peer-reviewed, and indexed by PubMed and Scopus, for example. However, it has some radical features that set it apart. It allows authors to have complete control over the publication process, writing the paper and determining the final format, all within the PLOS Currents platform. Like PLOS ONE, it doesn’t try to make the call on perceived impact, but unlike PLOS ONE, it will consider simpler, less narrative items for publication – “single figures or experiments, research in progress, protocols, datasets”. In addition, a structured versioning system means that you can go on updating papers after their initial publication. I’ve half a mind to dust off some of my old autorads…

Betancur-R., R., Broughton, R., Wiley, E., Carpenter, K., López, J., Li, C., Holcroft, N., Arcila, D., Sanciangco, M., Cureton II, J., Zhang, F., Buser, T., Campbell, M., Ballesteros, J., Roa-Varon, A., Willis, S., Borden, W., Rowley, T., Reneau, P., Hough, D., Lu, G., Grande, T., Arratia, G., & Ortí, G. (2013). The Tree of Life and a New Classification of Bony Fishes PLoS Currents DOI: 10.1371/currents.tol.53ba26640df0ccaee75bb165c8c26288

Broughton, R., Betancur-R., R., Li, C., Arratia, G., & Ortí, G. (2013). Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis reveals the pattern and tempo of bony fish evolution PLoS Currents DOI: 10.1371/currents.tol.2ca8041495ffafd0c92756e75247483e

[…] trees” that show the evolutionary relationship between different species (see a previous Biologue post of mine for more about phylogenetic […]